Taiji Wu Style

Bart Saris

I. INTRODUCTION

About the author and the "European School for Original Wu style Tai Chi Chuan"

The author of these articles, Bart Saris, has been practicing t.c.c. for about 13 years now. The first 4 to 5 years he studied a Yang style variant: a so called “simplified” form designed by Cheng Man Ching, which was at the time the only form available. During that time he attended the lessons of several (Dutch) teachers, and visited workshops of people like Benjamin Lo. After a number of years he started to feel a growing sense of discontent, as he discovered that his native teachers were by no means able to explain in a satisfactory way the know-how of the postures. Also he became a feeling that the contacts with the “source”, in this case the master students of Cheng Man Ching, were too short and superficial to be fruitful.

Last but not least he was deeply interested in Tui-Shou (pushing hands), a discipline of which there was only very shallow material available.

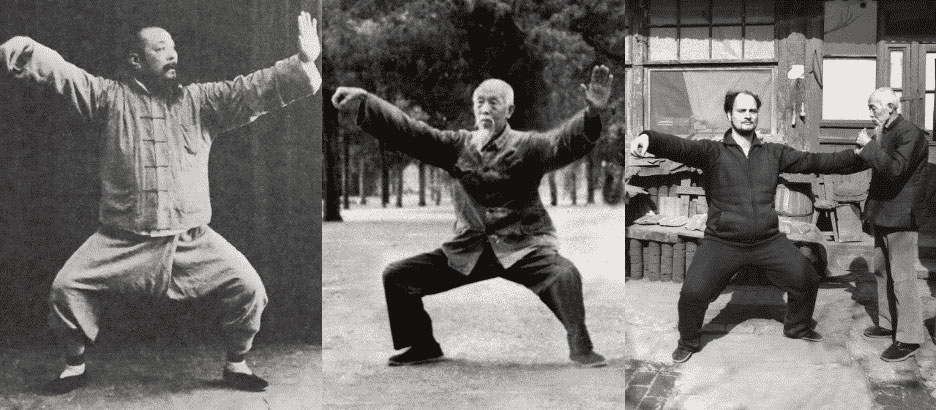

By the time, however, he was actually planning to spend a few years in China, his problem got solved in 1986 when he met Master Ma Jiang-Bao in Düsseldorf, after having seen him demonstrate in Amsterdam with his father, the then 84 years old Ma Yueh-Liang. He has mainly been practicing Wu style t.c.c. under Ma Jiang-Bao’s guidance ever since, first in Germany and the last 7 years in the Netherlands.

The series of three articles he wrote, are meant to raise the level of awareness about Original Wu style t.c.c. in Europe, which is still quite low, most people are only acquainted with Yang style versions. (After all, Yang style and its spin-off was the first to reach the West).

The first article deals with some contemporary (modern) t.c.c. history, to give the original Wu style its proper place in the spectrum of styles.

The second article discusses some technical aspects, which are specific for this Wu style.

Finally the third article describes the state of affairs after Ma Jiang-Bao has been teaching for 9 years in Europe.

II. "The original Wu-style and the modern history of tai-chi-chuan: "The Yang and Wu families"

1. Introduction: modern history of t.c.c. starting with Yang Lu-Chan.

When speaking about tai-chi-chuan variants one usually mentions a number of so-called “recognized” styles. The ones mostly mentioned are Yang style, Wu style and Chen style, these three being the best known around the world, at least by name. Apart from these also the Sun style and the How style are in general considered to be “official”styles. This enumeration is always accompanied with the seemingly standard remarks, that first of all the original Chen style would be the oldest, and at the same time more seldom practiced style of the three main variants. Also it would have served as a starting point for all other forms of modern t.c.c., including modern Chen style t.c.c.. There is no doubt that this is a correct statement, as all other styles, including the more popular ones, can in one way or the other be traced back to Yang Lu-Chan. He in turn learned his t.c.c. during an apprenticeship of many years within the Chen family.*

*note In Tai Chi Magazine of april 1984, Fu Zhong-Wen refuted the legend about Yang Lu-Chan having learned his t.c.c. only by secretly watching the Chen family exercise at night. (The true history of the Yang-style).

Yang Lu-Chan learned the art from Chen Chang-Hsing. This person had thorough knowledge of the “family secrets” and was principally prepared to pass them on to whoever had the talent and interest and would be persevering enough to work intensively for many years on end. After having lived and studied for 18 years in the Chen village, Yang Lu-Chan was ready at last: nobody would be able to defeat or “touch” him anymore. That at least was the distinct opinion of Chen Chang-Hsing after personally teaching and supervising Yang for a last period of six years, convinced by his diligence and possibilities. From that moment on, Yang Lu-Chan incorporated the family secrets: in fact, he had become “family” himself.

2. The Spreading starts: Two Wu styles?

Afterwards with Yang the art of t.c.c. started to spread, initially in China only, but nowadays assuming worldwide proportions to the point that the Chinese actually think about trying to get t.c.c. on the Olympic agenda.

Presently what is known as Yang style includes a vast number of different variants all of which claim to be rooted in Yang’s t.c.c.. Taken together they represent the most popular form of t.c.c. in our days, followed in second place by the Wu style.

To avoid misunderstanding it should be pointed out which Wu style is meant here, because there are two quite different looking forms of t.c.c., each of them rightfully named “Wu style”. Each one though has its own history.

a) Wu Yu-Hsing

One starts with Wu Yu-Hsing (1812-1880), who studied with Yang Lu-Chan. The name of this Wu is forever connected with the finding of the manuscript of Wang Tsung-Yueh’s “Classics of Tai Chi Chuan” in a salt shop. It seems that Yang Lu-Chan confirmed the value of this piece of writing, which has been a touchstone for correct t.c.c. ever since. The variant of t.c.c. that this Wu created has been practiced up till now, on a very limited scale. Related versions like Sun and How style have not yet become as widespread as the other two styles either.

To be intensively engaged in the old martial arts was, at the end of the last century, a privilege mainly reserved for the Chinese rich and idle, the ones with enough money and leisuretime. Wu Yu-Hsing was a typical member of this rich upper-class. Yang Lu-Chan’s skills were so outstanding, that he was invited by this Wu to be his teacher. Through Wu’s excellent connections Yang was then appointed to be an important martial arts instructor for the nobility, the officers and other important people, in and around the imperial court.

b) Wu Chuan-Yuo

The founding father however of the other, currently more practiced Wu style which is the main subject of these articles, is a Manchu captain of the imperial guard named Chuan-Yuo (1832-1902); He too was a student of Yang Lu-Chan. His name is usually mentioned with two other master-students of Yang Lu-Chan, known as Wan Chun and Liu San.

It is said that each of those three inherited a characteristic skill of their teacher: one obtained the “energetic”, the other the “offensive”, and Chuan Yuo the “neutralizing” skill. Together they were compared to respectively the “muscles”, the “bones” and the “skin” of tai chi chuan as a martial system.

In those days China was still very much a rigid class society. Consequently Yang’s name as a teacher was allowed to be connected directly only with the élite, the court clique that he taught. An exception was made on behalf of his two sons. The three master students mentioned before, who were intimately related to Yang-Lu-Chan, would for this reason be officially called students of his son Yang Ban-Hou. Nevertheless they were intensively instructed and attended to by Yang Lu-Chan himself. As said, Chuan Yuo was one of those. A family-anecdote tells about Chuan Yuo doing Tui-Shou training with Lu-Chan’s son Yang Ban-Hou. Continuously “pushed-out” by Chuan-Yuo, after a while Yang Ban-Hou complained to his father saying that he should better keep the family secrets. Yang Lu-Chan’s reprimand carries a clear message: “I also was somebody from outside the family, who earned the family secrets by studying very hard and very long”.

The t.c.c.-style that descended from Chuan Yuo, was connected to the name “Wu” only one generation later, when his son changed the family name to bring it in accordance with the Chinese pronunciation of their Manchu name. This son Wu Chian-Chuan (1870-1942) is regarded within the family to be the real founder of the Wu style. During his lifetime he became one of the most famous tai chi chuan masters of his days. From a very early age he was trained by his father and he also practiced with Yang Lu-Chan’s sons, Yang Chien-Hou and Yang Ban-Hou. Both families had become very much engaged in each other, also because the circle of high-level t.c.c. adepts was still very small in that period. Therefore practicing together was as normal as it was necessary to maintain and develop the art. For instance, the sons of Yang Chien-Hou, Yang Cheng-Fu and Yang Shao-Hao, would be regular visitors to Wu Chian-Chuan’s home during the period that he lived in Peking. He lived there because in the early days of the Chinese Republic a man named Xi Yui-Seng, who was a follower of the Yang family, founded the Institute for Athletic Investigation in Peking and then invited Yang Cheng-Fu, Yang Shao-Hao, Wu Chian-Chuan and Sun Lu-Tang to take care of the t.c.c. classes.

From that time on t.c.c. was also taught to the public. With this the “closed doors” strategy came largely to an end, although distinction is sometimes still made between paying students and those that establish the kind of personal relationship with their teacher that turns them into pupils, fit for in depth transmission and life long cooperation. (Ma Yueh-Liang in German “Martial Arts”, Nov/Dec 1986).

Anyway, from then on t.c.c. started to spread all over China and afterwards over the rest of the world.

Looking at the quality of the people initially involved in the Institute, it is no wonder that three of them enriched the world with a new particular style of the art. The cooperation was very intensive. Yang Cheng-Fu and Wu Chian-Chuan would be playing Tui Shou together every week. For that purpose they would retreat to a secluded room, from where outsiders could frequently hear them shout “hao hao”, which means “good good”. If, however, Yang Shao-Hao the elder of the two brothers paid a visit, there would be no practicing. At best there would be conversation on t.c.c. matters with Wu Chian-Chuan. These two great masters of the first half of the Twentieth Century hardly ever felt each others chi. Why? That is hard to say; maybe there was no necessity or too much respect on both sides. So much is certain that Yang Shao-Hao did not believe in the way of “making t.c.c. suitable for the public”, which was the route both Yang Cheng-Fu and Wu Chian-Chuan chose. So maybe that was one of the reasons. Both families continued the pattern of practicing together also in the next generation. Wu Gong-Yi for instance, Wu Chian-Chuan’s son, became very friendly with the 30-year elder Yang Shao-Hao and practiced quite a lot with him. We can assume that he combined what he learned from his father with Yang Shao-Hao’s material.

According to some people this was evident in his form. Yang Shao-Hao, being a master of the “old fashion”, stuck exclusively to the original “fast” form. He opposed the idea of making t.c.c. popular through adaptation of the forms, as his younger brother did, who thus became the founder of what nevertheless nowadays is remarkably called “traditional Yang style”.

Besides Gong-Yi, Wu Chian-Chuan had two other master students: his daughter Wu Ying-Hwa and her husband Ma Yueh-Liang. Both grand masters are now in their nineties, still very active and their t.c.c. is better than ever! For years on end Ma Yueh-Liang was the assistant of Wu Chian-Chuan with whom he travelled the country for demonstration purposes. After Wu Chian-Chuan’s death this daughter and her husband succeeded him as promoters and supervisors of Wu’s t.c.c., first on the mainland and later also outside China.

3. The original forms and the arise of "styles".

So it appears that the great masters frequently practiced together. They themselves did not make the division of t.c.c. into styles, for that matter. The students did that. At a certain point they started to define their t.c.c. using the names of their teacher, thus creating the styles as we know them now. For the masters themselves, there was (and is) basically just one t.c.c..

That t.c.c. originally consisted of the whole integral, coherent set of forms and exercises that Yang Lu-Chan received from his teacher Chen Chang-Hsing. Maybe this set has been enriched with the fruits of later developments, but it has not grown smaller, as if “later developments” could replace the original set or make parts of it superfluous! A central position in this original set was taken by the “fast” solo form. It should be noted here, that the forms designedd especially for slow practice, which are so typical for present t.c.c., still had to be “invented”. The expression “fast” however should not be taken too literally. Although this form may be practiced very fast indeed, it can also and should be done very slowly for exercise purposes. Besides there are cooling down and warming up Chi Kung exercises, several sabre/knife forms, lance/stick forms, sword forms and the Tui-Shou and Ta-Lu sets, which by themselves already make for an extensive system. At last there is a very sophisticated combat exercise called Lan-Cai-Hua, in which the art may reach the acme of martial perfection and effectiveness. This exercise is hardly ever shown in public and even more seldom taught to people from outside the family, at least until now.

The fan form and San Shou are products of more recent developments. They are absent in the original set.

Of old the family structure would be very important to uphold all this as an integral system and pass it on unharmed. In the third generation however of the Yangs as a t.c.c. family the unavoidable happened. Yang Shao-Hao, as far as we know, did not have any master students, except maybe Wu Kung Yi. His character, way of life, and orientation did not allow him to have any. With his decease, the old-fashioned way of practicing the original sets may have got lost within the Yang family. If not, they have been successful in hiding it.

For instance, I do not know of any Yang style student that has been taught the original fast form, but I do know at least one that did create his ówn fast t.c.c.. It seems that one Ying Chieh-Tung, a student of Yang Cheng-Fu created two fast forms while in exile during World War II. Judging however by the pictures I saw in Tai Chi magazine of Oct. 1983, it does not look quite the same as the original fast form, so there may be no direct link. What happened in the early days of the Institute for Athletic Investigation is that Yang Cheng-Fu, Yang Shao-Hao’s brother, made changes in the original fast form to make t.c.c. more accessible for the general public. For that purpose, he sacrificed certain (martial) aspects to get a more direct return as a health exercise. Thus he came up with a form meant to be practiced at a slow and even pace. Further development and simplifying of this form especially after Yang Cheng-Fu’s death has led to popularizatoin as well as watering down: the original t.c.c. set has become rather disintegrated ever since,( within Yang circles at least ).

Like Yang Cheng-Fu, who is considered to be the father of the modern Yang style, Wu Chian-Chuan also reconstructed and enriched the art, in a different way though. He left the original set untouched to be studied by the family and by anybody with the courage to get really involved in the art. Besides, he also designed a solo form exclusively meant for slow practice, taking the original fast form as a starting point*.

*note By the way, it is not at all certain that Yang Cheng-Fu actually wanted to replace the fast form with his own design. Maybe he only wanted to reserve it for the family. After all the Wu family on their part also did not give it to the public until the Eighties. On the other hand there may also have been a physical inability to teach it, because of his tremendous size and weight in later years.

His goal too was to make t.c.c. accessible to more people and at the same time promote the development of “soft” chi and spiritual and physical well-being. Like Yang Cheng-Fu, he left out the jumps, the speed changes and stamping movements. However he modified without making concessions on the martial aspects of any detail in the movements. He made the movements smaller and more compact. Thus his form became as it were “written” for short range body contact. This way slow solo form and Tui-Shou became very much complementary to each other. In doing so, he killed two birds with one stone.

To prevent misunderstanding: the effect of saving space in the circling body movements and of greater compactness is only valid when the slow Wu form is compared to the original fast form. As far as the Yang style slow form is concerned however, the comparison doesnot fit. As a matter of fact, most circling body movements in the slow Wu style form are more spacious than the corresponding movements of the slow Yang style variants I have met so far. (Cheng Man-Ching, W.W. Chen, Yang Zen-Chuo, Fu Sheng-Yuan, KH Thu, Peking form etc.)

It shows clearly in the “parting leg” postures and in postures like “White Crane flaps its wings”, “Jade Girl works at the Shuttles”, “Cloud hands”, “Golden Cockerel stand on one leg”, etc.. Nevertheless sometimes the movements of the Wu style slow form lóok as if they were indeed more compact, when compared to the Yang style slow form.

The space saving impression that Wu style slow form makes, is because of the fact that in Wu style the elbows are never spread out beside the body as is normal in some Yang style variants. Also there is a clear difference in the method of stepping forward or backward. Yang style often uses strong hip/torso turning while making spacious arm movements towards the back. In this case Wu style slow form is indeed space saving: while stepping forward or backward torso and head/vision are not turned aside but kept vigilantly directed to the place in front where the “opponent” is standing. The arms do not make any dashing backward arching, but start their sober part in the action from their naturally protective function near the body.

A last reason for the more spacious impression of at least some Yang styles can be found in the fact that Yang Cheng-Fu chose low postures and large foot steps, where as in Wu style slow form, Wu Chian-Chuan prescribed less low postures and foot stepping that generally does not exceed one and a half lengths between front foot heel and back foot toe. Nevertheless as said, most circling body movements in Wu style slow form are more spacious than the corresponding ones in Yang style. This is even more so in the Wu style fast form: this form being designed to efficiently cover as large a space as possible around the body.

Kumar Frances, comparing Chen Yang and Wu styles, is not very far off the target, I think, when he supposes that in Chen style the emphasis traditionally is on developing “hard” internal energy first. This shows in the explosive, shocking and turning techniques. The “soft” internal energy would have to arise after the “hard”one has fully developed. According to Kumar Frances, Yang Lu-Chan took a somewhat different direction. The “soft” would still have to be produced from the “hard” but as synchrone as possible. This also reflects in Yang Cheng-Fu’s slow form, I think, as he combined relaxed soft movements with extremely low postures. Wu Chian-Chuan, following the footsteps of his father, emphasized the direct opposite of the spectrum: first of all it was his intention to have “soft” healing energy developed. Only afterwards would there be attention for the arise of “hard” internal energy. (Kumar Frances in T’ai Chi Magazine, Oct. ’87, page 10 etc.). As a matter of fact, this approach is clearly recognizable in Wu style t.c.c. as it descended from Wu Chian-Chuan, and is now being taught by his grandson Ma Jiang-Bao in Europe. It shows, especially in the slow solo form, but also in the relaxed approach to Tui-Shou. Wu style Tui-Shou requires strict central equilibrium and connectedness throughout the body. Also there should be inner silence, subtlety and above all softness while practicing the many interweaving patterns of movements. Tui-Shou with steps and Ta-Lu especially promote alertness and “sticking” energy. At last everything comes together in Lan-Cai-Hua, a sparring technique and combat exercise in which all preceding practice culminates and where hard internal energy is developed. It is said that the power of it is like the flow of a great river and that the strategy is so complex that it is hardly expressable in words.

4. Disintegration.

Because of the disintegration, at present, of t.c.c. as a total, all embracing system, even in China it is now extremely difficult to find a master who has learned the whole integral set, and moreover would be willing and capable to share it with students. The irony of fate however wants that right now in Europe we have our noses right on top of it. Ma Jiang-Bao, Wu Chian-Chuan’s grandson, is firmly rooted in the Yang/Wu family tradition. His parents Ma Yueh-Liang and Wu Ying Hwa are still living grandmasters, who with unending energy keep showing the benefits of Wu Chian-Chuan’s t.c.c., which they incorporate. For more than fifty years they have been doing that, inside as well as outside China. They advocate a t.c.c. that preserves Yang Lu-Chan’s heritage essentially unharmed, with Wu Chian-Chuan’s unique creation added to it: the Wu style slow solo form.

At present Ma Jiang-Bao lives in the Netherlands on a permanent basis and he is willing to share his knowledge and art with us, if only we are ready to let go the idea that we are well on our way and already know what t.c.c. is all about. The truth of the matter is that most of us in the West have barely scratched the surface until now. We still have to find our way in past the doorstep.

5. Some misunderstandings.

What is left on this occasion, is to dispose of some misunderstandings that came into the world due to a few inaccuracies that can be found in You Tsung-Hwa’s widely spread book “The Tao of T’ai Chi Chuan” (edition 19, page 43/44). The first misunderstanding concerns his suggestion that Wu Chian-Chuan’s form should be considered to be a version of Yang Cheng-Fu’s t.c.c.. This is not correct, since there is no way that Wu Chian-Chuan can be considered to have been one of Yang Cheng-Fu’s students. As I pointed out before, there was a time that both men actually practiced together, but this was done on a basis of equality and in a spirit of cooperation. In close contact with each other, each one developed his own modified slow form, each one taking off from his own specific view, but both taking the original fast form as a starting point. The views each one brought in, were based on each families’ tradition. Personal interest and ability too played a role in the respective formations. Thus it happened that, though leaving from the same base, Yang’s and Wu’s slow solo forms look quite different. Further it is not improbable that Yang’s ever increasing shape may have had an involuntary influence on the way he conceived his form originally and changed it considerably in later years. I shall return to this subject on the next occasion. A second argument against You’s opinion is, that after all Wu You-Hsing as well as Wu Chuan-Yuo were students of Yang Lu-Chan. Leaving from there it does not seem very obvious to treat the t.c.c. version that started with the first one as a particular style, as You does, whereas the t.c.c. line starting with the other one would have to be considered a Yang version.

If you want, there would be more logic in considering both “Wu styles” to be Yang style versions, which they are strictly speaking, if one takes Yang Lu-Chan as the point of departure. However, one step further back all modern t.c.c. styles are Chen style versions!

Be this as it may, nowadays bóth Wu styles are generally seen as different styles, which is right looking from the point of view of the unmistakable differences there are between Yang and Chen styles.

The second misunderstanding, given birth to by You Tsung-Hwa as well, concerns his judgement of the quality of the t.c.c. of Wu Gong-Yi, Wu Chian-Chuan’s eldest son.

According to You Tsung-Hwa, Gong-Yi’s t.c.c. would have been of significantly less quality than his father’s. I don’t know by what authority You makes statements like this, unless his own t.c.c. is of a standard comparable to Gong-Yi’s. I very much doubt this to be the case, since he, by his own statements, learned by picking up bits and pieces here and there, choosing never to be directly guided by any master of the art whatsoever, studying and researching on his own.

This way of going at it may surely produce some benefit, but it may also set limits to one’s development ultimately. If pictures can tell a story, then it can clearly be seen in You’s pictures, published in T’ai chi Magazine of August 1992, that they lack the unmistakable radiation of inner strength that is so typical for the pictures of all the great t.c.c. masters, including those of Wu Gong-Yi. Anyway, as far as the practice of t.c.c. leads up to martial quality, Gong-Yi’s t.c.c. must have been in pretty good shape, and he didn’t bother to hide that either. When still young he would, on occasion, seek confrontation with the authorities of every kind of martial field, and he never lost. Even when he was older he did not shy at challenges, though he did not seek them anymore by then either. He was quite famous for settling those challenges in big arenas with maybe ten or twenty thousand people watching. All this gave rise to a number of anecdotes about his martial powers, which are still being cherished within the Wu family. The same martial quality of Gong-Yi brought it about that in Hong Kong as well as in large parts of Southeast Asia Wu style t.c.c. has become the most practiced one.

By the way, when only twenty years old, Wu Gong-Yi was already leading the martial arts department of the most important military academy of those days in China. There was a good reason for that too. Apart from all this, he changed and modified his father’s form somewhat according to his own views, to make t.c.c. even more accessible. For that purpose he heightened the postures considerably once again and made the movements very small and compact indeed. Judging by the available pictures, however, it looks like he only consistently went further in the direction his father initiated, going as far as possible without impairing the art. Once landed in Hong Kong, however, he saw himself at a certain point put to the task of teaching several hundreds of persons at the same time. To be able to do this, he designed a special method for that, which later would be called “one-two-three” form or also sometimes “square” form. It was meant for didactical purposes only, to provide “basics” to be worked out at a later stage. Connectedness, roundness and fluidity had to be brought in afterwards.

Of course a number of people stopped following the lessons before arriving at that point. Some of these started passing on this didactical method as if it were Wu Kung-Yi’s authentic solo form, thus causing the kind of misunderstanding that evidently mislead You Tsung Hwa too, and with him many that read his book.

Meanwhile however one must regretfully admit that Wu Kung-Yi’s teaching method started to lead its own life including variants and variants on variants.

A comparable fanning and simplifying also took place in the Yang style for that matter, and is still going on as this is being written. All that, however, did nót affect the development of Wu style t.c.c. in the People’s Republic, where Wu Ying-Hwa and Ma Yueh-Liang faithfully administered the heritage of Wu Chian-Chuan and are still busy doing so. There Wu Chian-Chuan’s t.c.c. was and is being passed on without basic changes whatsoever. Right now master Ma Jiang-Bao, their son, is doing the same in Europe from his residence in the Netherlands (The Hague).

III. Some striking characteristics of Wu Chian-Chuan's Original Wu style tai chi chuan

1. Introduction.

This is not the occasion to make a detailed comparison between the original Wu style and other established t.c.c. styles. Howeverin the original Wu style there are a few “niceties” that at first glance already appear to be different from other styles. I would like to make a few introductory remarks on some of these specific characteristics.

I shall try to indicate why as well as I can, and I shall explain where in my opinion those things are placed within the general practice of t.c.c..

2. Archery stance.

First of all it is necessary to look at the original Wu style version of the archery stance. The Wu style student makes this stance standing slightly forward. The silhouette, viewed from the side, is such that the body forms a straight line from the heel of the back leg right up to the top of the head. The toes of both feet at the same time point equally to the front, the feet being in parallel position. This stance which is used, for instance, while doing “brush knee” or “twist step”, looks quite different from the equivalent in other styles. In some modern Yang style variants for example, particularly Cheng-Man-Ching’s version, an upright body position from the hips upward is stressed, so as to make head and trunk perpendicular to the surface one is standing on. Considering the fact that the upright archery stance position is the one predominantly used in the West, for many people it carries the notion that this is the only proper way to do it, while practicing t.c.c.. On a closer look at the issue, this is certainly not the case. When discussing the upright position, it is often argued that leaning forward would be incompatible with what the “classics” prescribe on this matter, especially where the position of the top of the head is mentioned, that should be held “as if suspended”, or where it says that the head should be lifted and the neck straightened. The position of the head (hui-lin-din-jin) is indeed extremely important and crucial for what happens before. However that does nót necessarily mean, that the upperbody should be kept upright at all times. The texts of the classics allow enough flexibility for both ways, since they are not unambiguous on the matter. Besides, the slanting way of doing the archery stance is definitely the older and original one. If we look back a little into the history of t.c.c., as we did in our first article, we see that the source of the Wu style way of doing the archery stance, a slanting can be found in the original “fast” form as it was practiced and passed on by Yang Lu-Chan. This “fast” form, that could be practiced slowly too, precedes all later, especially for slow practice designed forms*.

*note: That is, the Yang and Wu versions. I don’t know about the impact of these two forms on the modern slow Chen style or on the “other” Wu style.

In this fast form , the slanting body as well as the consistently parallel positioning of the feet can be traced back as characteristics. Of old, the fast form was practiced within both the Yang and Wu family. As far as the present is concerned, I am sure only about its being upheld within the Wu family. Since the Eighties it is also (sometimes) taught to “outsiders”, who have reached a certain level in the execution of the slow solo form. For Yang Cheng-Fu as well as for Wu Chian-Chuan this fast form served as a starting point from which each left to make t.c.c. available to the public by means of creating adapted slow forms. Both men wanted to meet the demands of the new times and the changing social situation. They wanted the public to be able to take advantage of the physical and spiritual benefits of regular t.c.c. practice, without necessarily having extensive preparation or even in ill health or old age.

As I see it, the resulting new forms have two faces. On the one hand they are most certainly the “real thing” in a condensed form. On the other hand they also have a distinct preparatory function for those who may want to deepen their t.c.c.-studies through the totality of the system. Not everybody agreed to the policy of making t.c.c. “digestible”. We know for instance that Yang Shao-Hao, Yang Cheng-Fu’s younger brother, always remained “faithful” to the old fast form. He ignored the new way. As he did not care about having students, it seems that he did not leave any master students either. Therefore it may very well be the case that with his death the practice of this form stopped within the Yang family, (though one cannot be sure about it). Be that as it may, the truth is, that the patterns of the movements of the fast form and the way they should be executed traditionally, do no longer fit in very well with the way Yang style is practiced nowadays, be it “traditional” or modern. There is too much of a gap.

3. Parallel foot position?

In the beginning Yang Cheng-Fu kept the slanting archery stance and almost parallel foot positions (Tai Chi Magazine, 1982 August; Wu Ta-Yeh and Teng Shu-Hsien on Yang Cheng-Fu’s early and later postures). Considering from where he left off, this is not surprising. However, if one chooses to enlarge the lateral distance between the feet, like he did, and at the same time keep the upper body and hips in the same direction, then it becomes increasingly difficult to keep the feet in a parallel position. Besides, problems are bound to arise when one wants to shift the weight to the back foot. When later on he chose a more upright position, it became virtually impossible nót to turn the backfoot to a diagonal direction: that is, if at the same time, one wants to relax the waist. As a matter of fact, later on his feet would make an almost 90 degree angle.

One of the consequences in doing so is, that in the archery stance as from then, the back foot no longer determines the direction of the upper body. This role is taken over by the front foot.

The slight slant never totally left Yang Cheng-Fu’s archery stance for that matter. Only later adaptations, like the one Cheng Man-Ching made, fully adopted the upright position of the body.

4. Improvements?

Although Yang Cheng-Fu himself would say that the development of his form showed an ongoing line of “improvements” in time, it may very well have been the case that part of these improvements were forced on him by physical necessity. Some people at least think that his ever growing weight and physical appearance are directly responsible for a few of them.

Be that as it may, one does not have to be a clairvoyant to be able to conclude, that his legendary weight and size in some way or other must have had an impact on, for instance, the center of gravity and the load-bearing of the front foot. A very corpulent person like Yang Cheng-Fu, when doing the archery stance the way it is done in the original Wu style, might feel he is toppling over the front foot. By inclining the body lessone may considerably diminish the pressure on the front foot by up to 30 percent doing the archery stance totally upright. The advantage in such a case is evident, since the center of gravity moves “inward” accordingly. Viewed this way, the tendency to incline less is only natural and perfectly legitimate, because it does not contradict the classics. However, creating an exclusive standard for “good” t.c.c. out of such adaptations, is not legitimate at all!

Nevertheless, that is exactly what is done by some modern Yang stylists, though through only ignorance I suppose, not through ill will.

Luckily, many of these kinds of misunderstanding that somehow sneaked in, while t.c.c. was being discovered in the West, rapidly lose ground, since more and more of the astonishingly multicolored thing that t.c.c. is, comes to light.

5. Wu Chian-Chuan's way.

The course that Wu Chian-Chuan took, is within the framework of the current Wu family approach ever since Wu Chuan-Yuo: the emphasis is always first of all on “soft” and healing internal energy. The neutralizing and transforming elements prevail at first: only later on the development of “hard” internal energy is promoted.

He wanted slow form t.c.c. in principle to be accessible even to the ill and weak and to be potentially healing.

Therefore like Yang Cheng-Fu, Wu Chian-Chuan also did away with jumps, stamping movements and speed changes. At the same time he made his postures a little higher, while the distance between the heel of the front foot and the toes of the back foot became 1 1/2 foot-length maximum. The space between them should be shoulder width most of the time. He kept the parallel position of the feet in the archery stance and the slightly inclining body, which makes for about 100-100% weight shifting back and forth. The movements became smaller and more compact compared to the fast form, making them very suitable for hand to hand martial contact. Hence their close connection to Tui Shou practice.

At the same time the original fast form was preserved untouched as part of the total system. The result was that he added without taking essential things away. There were good reasons for Wu Chian-Chuan to hold on to the slanting body line and the parallel feet in the archery stance.

For one thing, this is a perfectly natural stance: almost everybody who, for instance, would want to push a car over a certain distance, would spontaneously do that while taking this position. This is so because it is the most effective way to use one’s strength in a forward direction. Whereas, under the same conditions, the upright position of the body seems rather artificial for that purpose. The slanting body line is essential and so is the direction of the back foot. If one places that foot in a diagonal or right angle direction, then the exercising of strength in the same direction would logically demand for the use of the shoulder or the back (Kao), which is quite another, although also effective way of using one’s body within the framework of t.c.c..

6. Consequences of leaving parallel foot position and raising the upper body.

Leaving this natural way by raising the upper body and moving the toe of the back foot sideways, has other consequences too. While the diagonal positioning of the back foot is necessary to avoid tension in the lower back area when doing the upright archery stance and keep the heel of the back foot touching the floor, there are involuntary side effects. One is that the agile connectedness throughout the body, that runs via the waist gets lost very easily, because it becomes harder to control the turning of the upper body from the feet, using the waist as the turning point. This is an important issue, because it is connected to the ability to neutralize as well as to use power. The same disadvantage shows when the weight is shifted to the back foot, if that back foot points in a diagonal direction. The symmetry in view of the main direction gets lost in both cases, which causes a kind of disorientation. The result is that, if one turns the upper body, especially inward, an adversary may quite easily disturb one’s balance. Consequently a tendency arises to make the waist rigid and start to move hips, trunk and head as one whole. This way the function of the waist as the “commander” gets lost, to the point that even an established t.c.c. master like William Chen is still puzzled as to where this commander may have hidden itself. Right now he has decided that, for the moment, it has to be sought in the thigh (Tai Chi Magazine, June 1992, page 7).

Without the waist in control, neutralizing effects have to be realized from compensating movements, for instance from folding in the hip area (the groin) and from swaying the upper body in all kinds of eccentric directions. Also one sees people trying to gain stability by lowering their center of gravity as far as possible and making themselves as heavy and immobile as possible by “de-energizing”. Often this results in a “turtle”-like silhouette and creates unnecessary tension in the tendons which could be harmful. As I see it, the maximum advantage to be gained is perhaps some kind of “balance” during the form or pushing hands, but a lively “central equilibrium” is quite another matter.

For that, there has to be a permanent sense of relaxed connectedness throughout the entire body and the ability when pushed for instance, to regulate accurately the use of incoming energy, without having to concentrate on keeping one’s balance.

The use of the waist is crucial to this, among other things of course.

From experiencing both methods, I personally think that making the waist rigid and thus minimizing its controlling function has resulted in the “bull-fighting” so often referred to, when push hands tournaments are reviewed. The use of muscle power is a way to compensate for the lack of neutralizing ability, if one is determined not to lose a fight. The same can often be seen in push hands classes too!

7. "Connected" body movement.

In the original Wu style the parallel position of the feet and the slanting body in the archery stance facilitate the correct use of the waist, thus promoting connectedness and central equilibrium. This connectedness shows in the inner order of every movement. The expression for it in words is: hand-waist-foot (weight). The meaning is, that first the hand starts to move, activated by the foot, then the upperbody follows in a waist-controlled manner; after that, the hip/foot and/or weight follow.

The result is a continuous circulaaaation of energy throughout the body while moving, which in turn promotes the feeling of connectedness and equilibrium. If done properly, and all other requirements are met as well, then one does not have to “balance” either in form execution nor in pushing hands, because a definite sense of stability arises. It takes many years to achieve this. The proper use of the waist is by no means easy.

In the “classics” we read: “The motion should be rooted in the feet, released through the legs, controlled by the waist, and manifested through the fingers”.

If one compares this to what I described as the method used in Wu style, there may be a contradiction. There is, however, no real contradiction since both methods complement each other. Actually the “classics” describe only half the process, the outwardly non-visible internal half, that stands for connectedness within the body. This connectedness is technically already there before the actual movement becomes visible.

What I described as the Wu style method, on the other hand, stands for the other visible half of the movement that flows back into the feet. In the visible motion therefore things work the other way around: the hands start first and body and weight follow as described, controlled by the waist. This is the only way it can be if the movements are judged by martial criteria. Only if the movements are executed in the described manner one may one avoid being pushed or punched in the unprotected head or other body parts, something which will unfailingly happen if the hands are always the last to reach their destination.

Summarizing one might say that both founders of modern t.c.c. departed from the slanting way of doing the archery stance with a parallel foot positioning. Yang Cheng-Fu’s more upright postures in later years and consequently the different back foot positioning, may have been caused by the need to prevent the center of gravity from shifting too far ahead, due to his changing volume.

8. "The rigid waist": looking for an answer.

All this does not necessary mean after all, that Yang Cheng-Fu himself already blocked his waist and started to move hips and upper body as a rigid unit. As a matter of fact it is most unlikely that he did, when one considers the source he used, the fast form, that virtually cannot be executed without a flexible waist. His great Tui Shou skills also indicate otherwise, though from the outside the visible waist movements, circles and curves may eventually have become very small or even quite invisible due to internalization, as often seems to happen when t.c.c. mastery reaches its peak. I witnessed this phenomenon once when grandmaster Ma Yueh-Liang demonstrated his Tui Shou with his son Ma Jiang-Bao.

If Yang Cheng-Fu still twisted his waist, how then did the total blocking of it enter the modern Yang style?

A certain phenomenon that I observed, may provide a possible explanation. In the city where I live, there is a Pentjak Silat teacher who has a considerable number of students and is regarded as one of the best local specialists in his craft. Due to a motor-cycle accident, however, this man happens to be handicapped by a small physical deformity: one of his arms is about 3 inches shorter than the other. For himself there is no problem at all. He simply totallly adapted the way of executing his pentjak silat movements to compensate for this. As a result he is not at all hampered by his little handicap. Strikingly, however, almost all his students imitate these adaptations even to the point of exaggeration, although they themselves are blessed with perfectly normal arms. As a result his students look as if it is they who have one arm shorter than the other, not him! Also they show a tendency to consider the adapted way of playing pentjak silat to be the only right way to do it. The teacher on his part encourages this attitude. Thus the deviation has almost become the standard.

Something similar might have happened regarding some of the changes that Yang Cheng-Fu introduced, particularly those that may have arisen from physical necessity due to his altering body.

In quite the same way, by wrong imitation though rather comical in this case, a few misunderstandings have arisen about some of Wu Chian-Chuan’s postures, particularly the positioning of the hands and elbows and which way to look. What happened is that sometime in the Thirties Wu Chian-Chuan had photographs being taken of his postures. The resulting series of pictures has been published several times over the years, the last time in Wu Ying-Hwa and Ma Yueh-Liang’s book on Wu style t.c.c., that deals with forms, concepts and applications of the original Wu style, (S.H. Book Co., Hong Kong 1988). Both grandmasters are the parents of Ma Jiang-Bao, who has been my teacher for a number of years now.

On one occasion I pointed out to him that some of the postures in these photographs seem to deviate from what he taught us and that some of the details even seem to contradict certain important principles that run through the entire solo form. On hearing my comment he laughed heartily. The story behind it, as he told me, is that those pictures where taken in a studio. The photographer, an obstinate man, had his own definite view on picture making. So he had demands that did not always comply with Wu’s wishes.

He wanted for example that Wu Chian-Chuan’s face be visible at most times, not partially covered by hands or arms and he wanted him to look straight into the camera as often as possible. Also some pictures were taken at the wrong moment within the movements. The inaccuracies that some of the pictures show are the direct consequences of these proceedings. Therefore they should not be taken too seriously. Nevertheless a number of these same details became amplified, as is clearly reflected in some Wu style students, not lucky enough to receive the proper instruction and information.

Despite this, the series as a whole is certainly worth studying because of the marvelous radiation of Wu Chian-Chuan’s postures that clearly bring across the gist of what t.c.c. can be when internally perfected.

A last example of how things sometimes happen concerning the turning of the waist, comes from my own experience.

Before becoming a student of master Ma Jiang-Bao and the original Wu style, I had been practicing Cheng Man-Ching’s simplified Yang form for some 5 years. At that time Ma Jiang-Bao, Wu Chian-Chuan’s grandson, was still teaching in Düsseldorf, Germany. Until then people like Benjamin Lo and William Chen had been my t.c.c. role models. In the Yang style version they practice, the archery stance is an upright one and the body from the hips upward is moved as one whole under the slogan “turn, don’t twist”. The shoulders always have to be on the same plane as the hips, so I was taught.

During the first almost 2 years that I followed master Ma’s lessons, I did not even notice the difference in the way he moved! Though he would frequently mention during instruction that “the waist” had to be turned, which meant that the upper body had to be turned by twisting in the waist area, I automatically translated that for myself into “turn hips plus upper body”. Of course Wu style t.c.c. did not feel very comfortable as a consequence! When he showed the movements, the fact that I changed them into something entirely different escaped my attention completely. Apart from my having been wrongly programmed, there were two other reasons for this. First of all, master Ma is a fairly large and above all sturdily built person with a big belly, behind which the turning in the waist area is partly hidden. Besides, it is not the case that, while twisting in the waist area, the hip area is forced to be immobile. It rather loosely follows the rest of the body. In the movements the twisting of the waist area functions within the sequence “hand-trunk-foot/weight”. Taken together it was difficult for my biased eye to see exactly what happened. Also the issue did not have master Ma’s special attention at that moment, because of the way he structures his lessons.

In the first 1 1/2 years he is satisfied when people manage roughly to learn the sequence of the total solo form, which is quite enough to handle at that point considering the intensity of his approach during the weekly lessons.

The rest will have to be dealt with later, or as he says, one is supposed to start at least eight times all over again before the form “stands” on all levels, never to be involuntarily changed again.

The issue at stake came to light once we started partner work, the Tui-Shou (pushing hands).

With that, the necessity of real stability became apparent, as in doing Tui-Shou your partner will unfailingly reveal every flaw in your central equilibrium and the lack of neutralizing ability resulting from it. At last, after doubting a while, I posed some straight questions. Until then it had not even occurred to him that I had not understood something so evident right from the beginning. Until that moment he must have thought that I had some strange disability that seriously impeded my movements!

After I explained, it dawned on him too. He has given the matter due attention ever since, also when teaching beginners. The message may be clear. After all, Yang Cheng-Fu too was a teacher of the more corpulent kind, with whom the twisting of the waist may have been hidden behind his prosperous belly. Maybe for him too the, waist twisting question was so self-evident that it did not occur to him that it needed special attention. Also, in those days in China, asking questions was considered unpolite. Perhaps this whole business of immobilizing the waist area is based on the kind of misinterpretation and false imitation by students that happened to myself initially.

On the other hand I cannot believe that Yang Cheng-Fu himself was not fully aware of the proper use of the waist: for that to be the case, the points 3 and 7 taken together of his “ten important points”, are far too eloquent. They relate to relaxing the waist and the mutual following of upper and lower in a way that in fact perfectly depicts what is practiced in the original Wu style and what Yang surely practiced himself too.

9. Shifting weight and changing direction.

Closely related to physically being “connected” and twisting the waist, there is also the issue of shifting the weight and changing direction. In the original Wu style, changing direction is always made directly, no matter whether the full weight of the body is resting on the front or the back foot. There are obvious martial reasons for this. One might think that this practice, especially when the body has to be turned starting from a fully loaded front leg, would give cause to the kind of tai-chi knee injuries that according to recent t.c.c. literature should be a serious reason for our concern, since they occur far more often than we expected until now, (Tai Chi Magazine, Aug. 1992).

Everyday practice however shows, that changing direction in the original Wu style never creates problems of that kind. The main reason, I think, is to be found in the procedure itself. While turning and changing direction, the body has to be kept in a state of soft, flexible connectedness.

At the same time within the movement, the sequence hand-upperbody-hip-foot/weight has to be strictly observed, using the stretched back leg as a point of support, but without bringing extra weight on to it. During the movement the knee stays handsomely right above the turning foot so that the ligaments are not stretched in any damaging direction. The weight bearing leg is neither overextended nor twisted.

At the same time, while turning slowly, the body goes from a slanting position to a vertical one and then back to slanting, though this may not always be the case, for instance, in the fast form, where very fast turns may be made without erecting the body, but with equal ease and comfort. The role of the waist, the relaxed twisting of it, is crucial to all this.

With proper use of the waist there is no need for the knees to make any motions that do not conform to their structural specifications, like curvy-linear or rotational motions.

This is different in some t.c.c. versions where one is supposed to keep the shoulders above the hips at all times. When changing direction in that case, the turn has to be made by bringing the hip around, steering it from the weight-bearing foot or thigh, which is nearly impossible if the front leg is involved, that is, if one wants to keep one’s knees in one piece. Therefore the weight has to be brought at least partly to the back leg first, to enable the front foot to take another position, after which the weight can be brought back to the front foot to execute the rest of a (for instance 180-degree) turn. Even when proceeding this way, there is always the risk of a torque on the knee ligaments with each change of direction especially when the turn has to be of 180 degrees or more. The Wu style method does not have that disadvantage: changes of direction (orientation) can be made up to 270 degrees, without undue stress on the knees.

The use of auxiliary weight shifting causes the wobbling that is so typical for many modern t.c.c. versions, but that is absent in Wu style. In the original Wu style, weight shifting always had a direct martial meaning. It is my impression that these auxiliary movements do not always have such functions and may sometimes be a hindrance, for instance, when sticking energy has to be applied.

There are no superfluous details to be found in Wu Chian-Chuan’s form. Every movement and every detail within each movement serves the functioning of the body as one whole, well connected unit with internal energy circulating permanently through.

Also there is a clear martial function for every single detail. Formerly when I practiced Cheng Man-Ching’s Yang style, there were often no satisfactory answers to questions about why certain things had to be done exactly that way. Most of the time answers would be vague and/or meaningless. Often one had to be content with the explanation that the instructor himself had learned it this way from hís teacher and the teacher in turn from hís teacher. Benjamin Lo, for example would say in the end, that the “professor” used to do it that way: end of discussion.

Also it would often be the case that the teachers disagreed among themselves about what it was they had learned, so……

With master Ma Jiang-Bao there are no such objections. there is no need to take anything on authority, because he is perfectly able to put every detail in its right perspective, practically as well as theoretically. On the other hand he often even does not have to give a full explanation himself.

What happens is that master Ma’s hands-on corrections are so accurate and eloquent in themselves, that it at once becomes clear why things have to be done as he points out: not because hé says so, but because the body itself communicates the correctness of it all directly. It does so by making one aware of a feeling of being internally “connected” and of the energy flow that goes with it. At those moments t.c.c. becomes as perceptible as the instructor itself, so to speak, felt directlyin the postures and movements that tell you: this is the way I want to be practiced. It goes without saying, that these are inspiring experiences, that gives one a sense of being on the right track at any rate. And was not the importance of being on the right track, and staying there while learning t.c.c., stated by the “Classics” as an imperative?

IV. Original Wu style tai chi chuan in Europe: the present state of affairs

By now, Wu style master Ma Jiang-Bao, grandson of Wu Chian-Chuan, has been staying and teaching in Europe for about 9 years. For 7 years he has been living in the Netherlands. The first 2 years he lived and taught in Germany, in the city of Düsseldorf.

During that 9 year period, gradually a nucleus of students from different countries has been forming, mainly consisting of people that are aware of the unique opportunity that his permanent stay in western Europe offers to their t.c.c. studies.

They are determined to seize this opportunity and have first hand instruction in all the ins and outs of the extremely versatile martial art that t.c.c. undoubtedly is. With master Ma Jiang-Bao, for the first time there is somebody living in Europe on a permanent basis, who is a direct descendent of one of the main Tai-Chi families and who incorporates the whole integral system of tai chi chuan. Moreover, he has the ability, the experience and the willingness to be a teacher.

Everybody who has been engaged in t.c.c. for a longer period of time, knows that 8 years is fairly short in terms of time needed to build up real t.c.c. skills, unless maybe one were to be instructed every single day and would be able to practice every day too for many hours on end. As it is, however, we deem ourselves already very lucky to have at least a few hours of real good instruction every week, thus receiving more than enough material to practice with throughout the week, everybody as much as he or she can. One might say, that this way the seed has been sown and that the first plants have started to grow firmly. It still may take a number of years for the first flowers to appear, but they will, there is no doubt about that.

Although master Ma’s stay in Germany lasted only 2 years, a considerable part of his momentary students is still German. Besides German students, there are also French, English, some Swiss and of course Dutch students by now. Though the number of students that are directly taught by master Ma on a weekly basis is growing steadily, it is not increasing as quickly as one might wish, or expect. Most of the Dutch students live in the district “Noord-Limburg”, where they form one group of students together with the Germans residing in the Ruhr area, coming over from cities like Düsseldorf, Duisburg, Essen, Wuppertal etc. Besides this larger group, there are smaller ones in the Dutch districts The Hague, Rotterdam-Dordrecht and Arnhem. Master Ma is also active within the Dutch Chinese community, that is in fact directly responsible for his staying in the Netherlands by having invited him. The scope of his activities there however is largely beyond my sight, so I cannot be specific on that.

By now, a few pupils, who have attained the proper level, have successfully taken up original Wu style instruction in the Ruhr area, in South Germany and in the South of the Netherlands, of course under master Ma’s direct supervision.

It is remarkable, by the way, that apart from a few exceptions, almost none of his students come from existing t.c.c. circles, which in the Netherlands are mostly Yang style students of any kind.

A substantial portion, however, of his pupils comes from the “external” martial arts setting, people that have been practicing for instance shaolin, karate, pentjak silat or Aikido for many years. Most of them got somehow stuck in their development, because they were unable to find somebody within reach to assist in further progress, or because they reached an age where the body starts to protest vehemently the rough physical training methods that are usually applied. Practicing t.c.c. with master Ma offers them the new perspective that they were looking for, providing them with the answers to martial arts questions they were vainly looking for within their own discipline.

Apart from these, there are of course the fresh starters, who come to t.c.c. for all the generally known reasons, varying from being attracted by the beauty of the movements to specific medical needs or martial expectations.

We sometimes wonder why it is , that so few people, who have already had t.c.c. experience for maybe several years, seek information, let alone join.

I am myself indeed one of those few that had been practicing Yang style for some 5 to 6 years, (in my case Cheng Man-Ching’s version), before I met master Ma and the original Wu style. I happened to meet him at the time in Amsterdam, where he gave demonstrations together with his father Ma Yueh-Liang, who was then 85 years old. For me it was at once clear, that for the first time I had witnessed the real thing.

I imagine that there must be people out there, just like myself at that time, who after having practiced t.c.c. for some time, develop an awareness of the well meant, but nevertheless, rather crippled and disintegrated way t.c.c. is often taught in this country as well as in the rest of Europe for that matter. Really qualified teachers are hardly available and the few that maybe are, have to come from overseas to stay for only a couple of days every year. So they are only available on a very limited scale mostly for short as well as very expensive seminars.

The material that is offered this way, is neither very consistent nor very coherent: in general it is scattered bits and pieces of different versions of the large whole that t.c.c. is.

I know of a number of people that try to build some kind of unity out of the different parts they have gathered this way, dancing so to say at different weddings, sometimes even bringing in material they “borrow” from outside, incorporating for instance Ba Gua and other methods, being unaware of the fact that t.c.c. in principle cán provide everything they need, because of its all embracing and systematic character.

The people that do not have the time or money to frequent these seminars, have to make do with what is offered by indeed enthusiastic and busy persons, but which is perforce second hand (if one is lucky), if not third or fourth hand material, alas, being presented as the real thing. And then I do not mention the kind of “teachers”, that learned their “skills”, while following a two, three or four week training stage somewhere, sometimes maybe even in China, and consequently advocate themselves as “experts” in the matter at hand. It is a pity, but I have to conclude, that the growing demand for t.c.c. instructors has led to increasing wild growth in Europe too.

I know for instance of somebody who learned somewhere the beginning part of the solo form up to a certain point and consequently started his own “white cloud” t.c.c. style, more or less called after the posture where he left the learning process. He is now successfully posing himself as an original grand master in his “style”.

Also there are people of external styles who, becoming aware of the growing interest in t.c.c., simply sort of slow down the speed of their external fighting and make other people believe that it is original t.c.c. they are doing, giving it an exotic name like for instance “Lama” style, the roots of which of course are proclaimed to be dating back a few thousand years in Chinese history.

For promotional purposes of their own, people like that incidently “borrow” photographs and health results of those who are doing the real thing. Or in some occasion the root problem is simply dodged by giving the activities a name like “practical” t.c.c. or something similar.

I firmly agree with Mike Sigman, who at last belled the cat in T’ai Chi Magazine of April 1992 (Wayfarer Publications, 2610 Silver Ridge Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90039), aiming at the situation in the USA. He eloquently marked the problem and tried to design a kind of profile of what one may or may not expect of a good t.c.c. teacher in terms of background, training, knowledge and level of skills.

It is not my intention on this occasion to initiate the same discussion on our side of the ocean, but I think all the same, that the time is near when the interest of proper development of t.c.c. in Europe will force us to contemplate the matter: our situation is not that different from the one in the USA.

Anyway, the availability of competent teachers in Europe is not so satisfying, that one could rightfully ignore an authentic master of one of the major family styles landing, so to speak, on one’s doorstep. In this case the one that “landed” is the grandson of the famous Wu Chian-Chuan, son of the equally famous grandmasters Ma Yueh-Liang and Wu Ying-Hua, Wu Chian-Chuan’s daughter, who are both in their nineties now but still “going very strong” t.c.c. wise, presenting themselves as living testimonies of what t.c.c. can do for mankind if properly practiced.

So the reaction on this event is rather poor. Why? One can only guess. There may be a number of reasons.

Perhaps there is an (exaggerated and misplaced) feeling of loyalty towards native instructors, that enhances a sense of betrayal if one were to inquire elsewhere?

Or maybe a kind of self complacency has crept in, that makes us overestimate our ability to “creatively” handle the material that we picked up randomly at seminars and workshops.

Maybe a reason is also to be found in the tendency towards the romantic spiritual and mysterious element, that somehow became too prominently connected to the practice of our noble art, as it drifted into the West, floating on the stream of the deconfessionalisation and the search for spiritual alternatives of the last two decades. This tendency echoes in what is presently known as “New Age tai chi”. The romantic spiritual view does not match very well with the “no nonsense” t.c.c. approach that master Ma, like all real masters, for instance advocates.

Of course, there is indeed a spiritual side to t.c.c.. After all its name “tai chi” denotes the “Grand-Ultimate” and the practicing of tai chi chuan has arisen from and is closely connected to the taoist philosophy and way of life.

The relationship between taoism and t.c.c. is not unlike the way japanese budo and zen-budism are intertwined. In t.c.c. the coherence is so strong to the point that the patterns of the movements themselves and the principles that govern them directly reflect the basics of taoism. What this means for t.c.c. as a martial art is laid down in the “classics”!

Nevertheless t.c.c. contains two at least equally important aspects, besides the spiritual one: the first one is the healing or health aspect that is expressed in the aiming for a long life or “eternal youth” (Yang San Feng).

The second aspect is the “chuan” element, the self-defence or martial art aspect.

Each of these three aspects is equally important, but at the same time if taken separately one does not necessarily need to practice t.c.c. to go after them. If one, for instance, is interested in spiritual matters, taoism provides one with countless meditation methods extensive literature and rites. Whoever is aiming for a long life and good health, or seeks curing of a specific disease, may choose out of a great number of special chi-kung exercises or look into traditional chinese taoist medicine in one of its forms. And last but not least, if one wants only martial techniques and ability, there is more at one’s disposal in China than can be learned in one lifetime.

However, if a person is after the understanding of all three aspects at the same time and the interaction between them, his best options are the so called internal martial arts, t.c.c. being the most prominent of these.

Within t.c.c. all three aspects are inseparably melted together in one whole. You cannot overemphasize or take out one of the ingredients without decisively crippling the system. Therefore, only a t.c.c. that represents all three elements in a balanced way and conforms to the “classics”, deserves in my opinion to be rightfully called t.c.c.. It is possible though that a student in the beginning is attracted by one or two facets, or even by something completely different, for instance the pure aesthetical beauty of its movements.

In what I called “New Age” tai chi, mainly a romantic spiritual and/or magical approach is stressed at the expense of the martial chi kung aspect of t.c.c.. The spiritual claim apparently being that t.c.c. is originally designed ónly to be a kind of “highway to enlightment”. One merely has to remind oneself of the opening sentence of the Tao Teh King, to see how absurd such a proposition is, because “The Tao (or Way) that can be said is not the eternal Tao”. This statement goes also for t.c.c. as an integral martial system, and even more so for a heavily mutilated system like the new-age variant, where the “meditative” aspect is being overemphasized, even singled out.

The result: lack of balance, showing in there being only soft without hard, only expansion without compression, only open without closed, and only empty without full. All this is reflected in the vagueness, in the lack of accuracy and the floating that the new-age forms show. In this scene “Tui-Shou” (pushing hands) is a dirty word, a curse, just like “t.c.c. fighting”.

Strictly speaking, however, I do not oppose the use of t.c.c. like movements for any purpose whatsoever, be it meditative, magical use, or for the fighting of stress or for anything else for that matter. I even can imagine that the movements lend themselves to a certain point for a number of these purposes and certainly can make one “feel good”, especially the slow forms.

However, whereas the utmost precise practice of the slow forms promote awareness and by being awake provokes a learning process that denies automatism and sleepiness, new-age “spiritual” t.c.c. practice, by its floating and vagueness, invites automatism and sleepiness back in, right through the front door sometimes even accompanied by music!

So if people want to do t.c.c.-like movements while dreaming about “enlightment” and “feeling really good”, it is all right with me. Only it should be clear that in such cases no longer t.c.c. is being practiced, but something else that only lóóks like t.c.c. at first glance, but in fact is not, because what people are aiming at is not the understanding of t.c.c. from the perspective of its three basic elements, but rather the “magic’ of it all. Therefore it also should not be called t.c.c..

By the way, as far as the “magic’ approach is concerned, I again have to agree with Mike Sigman, when he states that by digging our heels in at the magic we imagine, we may miss the real magic that exists.

Looking for the extraordinary, we may easily forget, that the sometimes magical seeming functions of t.c.c. are in fact inherent: that is, everyone is born with them. It is not a specific product of manmade means. (Wu Ying-Hwa in T’ai Chi magazine of April 1992, page 15).

If there is a key word in t.c.c., it is probably “natural ness”: t.c.c. is about restoring the inner and outer natural balance of our physical, mental and spiritual apparatus, the instrument so to say. Only on an undamaged and well-tuned instrument may one be able to play beatiful music.

As I see it, although integral t.c.c. has to comprise all three aspects mentioned before, the actual health, martial, and spiritual effects are really side-effects, the spin off of being engaged in a restoring process, that has to start with becoming aware of the imbalances on all levels, while practicing. Gradually the man made lumber that has been gathering on the instrument since day one of its being born, may loose some of its suffocating grip on the functioning of the same, thus becoming more and more the pliable instrument that nature originally designed for us and that indeed may work “miracles” in the end. It is hard work though, and much perseverance is needed: in fact, engaging in t.c.c. means engaging in a life long commitment, a never ending process.

Looking at what happened since master Ma Jiang-Bao arrived in Europe, we sometimes wonder if people are really interested in learning t.c.c., for what it really stands for.

An attempt, for instance to organize a weekend workshop with master Ma in Amsterdam at the end of ’91, totally failed: not enough people were interested.

A number of times however, he has been asked to teach only the Tui-Shou that the original Wu style is famous for: growing interest for the practical, martial side of t.c.c. has gradually brought to light that there are many legendary tales, but that in general there is very little real knowledge and ability available as far as this aspect of t.c.c. is concerned. Teachers with real t.c.c. skills, including Tui-Shou ability, are exceptionally hard to find. With Tui-Shou however the situation is even more difficult than with the forms; one simply cannot learn Tui-Shou on some spare afternoon, as seems to be possible with some “simplified” forms if one might believe certain people.

Tui-Shou is a very necessary, very difficult and very vast side of t.c.c. that is tightly connected to the forms and their precision. The relationship between the two is complementary. Tui-Shou however is much harder to learn and expert teaching on a personal basis is absolutely necessary since the “jing” (soft t’ai chi strength) has to be “fed”. Also while doing the forms, one may be able to “hide” oneself up to a certain degree by compensating lack of central equilibrium with balancing, more or less like a tight-rope walker. In Tui-Shou this is impossible: every lack of “connectedness” within the body as a whole, will unfailingly be exposed by our partners. Once we recognize this, the actual learning can start as a process where forms and Tui-Shou have a mutually fertilizing effect on each other, unless of course we start to compensate in Tui-Shou too, for instance by taking to brute force or “bull-fighting”.

Requests to teach Tui-Shou in an isolated way have until now always been denied by master Ma. It is his view, that in the original Wu style slow form and Tui-Shou (and all the rest too, for that matter) are one indivisible interconnected whole. Whoever wants to learn Wu style Tui-Shou, Ta-Lu, fast form, weapon forms and at last Lan-Cai-Hua, has to start with the first step: the slow solo form as designed by Wu Chian-Chuan which serves as center of the whole system, as summary, textbook and course of instruction at the same time, since it contains all the fundamentals of t.c.c. as it has been passed on until now within the family since Chuan-Yuo, one of the three famous master students of Yang Lu-Chan.

The only concession he may make to this, by exception, is that he sometimes allows somebody, if well prepared, to more or less start parallel learning of form and Tui-Shou, whereas normally it would take at least about 1 1/2 year before Tui-Shou is even introduced to a person.

For people who have already been practicing t.c.c. for some time, this procedure certainly forms a barrier, that has to be overcome. For nobody likes the idea of having to start all over again something of which he or she thought to be well on his/her way, already having put in considerable time, energy and money.

Of course, the time, energy and money that one spends, are by no means lost: I can talk from my own experience. However it may feel that way, initially, when regular confrontation with real expertise somewhat slows down our tendency towards “free finding and invention”, not to mention the dents that our image of “t.c.c. expert” gets from this.

In short, it takes some courage, a dose of open-mindedness and above all unlimited studiousness and love of work to take such a step.

Nevertheless, if anybody really wants to learn t.c.c…… I think, by the way, that it can be very meaningful to seriously practice more than one style at the same time, if one has the opportunity to do so. Something like that can give one beautiful material for study and comparison. When looked at against the background of the classical undisputed fundamentals, the division in “styles” is somewhat artificial anyway. In fact the division is more an invention of the students than of the masters themselves, who meet, recognize and value each other not on the basis of the style they practice but on the basis of personal “kung fu”. Meanwhile the most important thing a student is responsible for himself is to find the very best teacher he can possibly get, whatever the style this person may practice.

Summarizing one might say that there are two sides to master Ma’s 9 year’s stay in western Europe.

On one side there is the steadily growing number of students coming from different countries, that somehow “smell out” his presence and react to it. Also a stable nucleus has been formed of enthusiastic students that receive instruction on a weekly basis, who are ready to “go all the way” and work hard towards the understanding of t.c.c. in all its aspects.

On the other side, there is the somewhat poor response from “established” t.c.c. circles, from the people that one would expect to be most interested in his presence.

Whatever the reasons may be for this, it is also a fact that many potentially interested people may as yet still be unaware of him being available to them, since this fact, until now, has not been brought to anyone’s attention other than on a very limited scale.

Possibly, this writing of mine will bring a change, but I am not sure if master Ma is really keen on that. He himself gives the impression that he is not so much waiting for large numbers of students as for serious ones, who really want to learn and study hard.

As for me personally, the situation is perfect as it is: my needs are amply covered by first class instruction and almost undivided.